- Home

- Rabai al-Madhoun

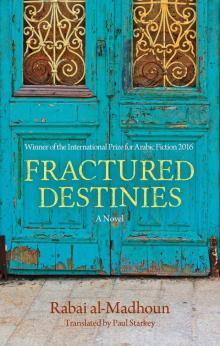

Fractured Destinies

Fractured Destinies Read online

Rabai al-Madhoun is a Palestinian writer and journalist, born in al-Majdal in southern Palestine in 1945. His family went to Gaza during the Nakba in 1948 and he later studied at Cairo and Alexandria universities, before being expelled from Egypt in 1970 for his political activities. He is the author of the acclaimed The Lady from Tel Aviv, which was shortlisted for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction in 2010, and has worked for a number of Arabic newspapers and magazines, including al-Quds al-Arabi, Al-Hayat, and Al-Sharq Al-Awsat. He currently lives in London, in the UK.

Paul Starkey, professor emeritus of Arabic at Durham University, England, won the 2015 Saif Ghobash Banipal Prize for Arabic Literary Translation. He has translated a number of contemporary Arabic writers, including Edwar al-Kharrat, Youssef Rakha, and Mansoura Ez-Eldin.

Fractured Destinies

Rabai al-Madhoun

Translated by

Paul Starkey

This electronic edition published in 2018 by

Hoopoe

113 Sharia Kasr el Aini, Cairo, Egypt

420 Fifth Avenue, New York, 10018

www.hoopoefiction.com

Hoopoe is an imprint of the American University in Cairo Press

www.aucpress.com

Copyright © 2015 by Rabai al-Madhoun

First published in Arabic in 2015 as Masa’ir: kunshirtu al-hulukust wa-l-nakba by al-Mu’assasa al-‘Arabiya li-l-Dirasat wa-l-Nashr

Protected under the Berne Convention

English translation copyright © 2018 by Paul Starkey

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978 977 416 862 8

eISBN: 978 161 797 878 4

Version 1

First Movement

1

Ivana Ardakian Littlehouse

As soon as Julie’s foot touched the first step of the rusty iron staircase leading up to the door of the house—pale blue, like a sky hesitating between winter and summer—the bells of Acre’s old churches began to peal, announcing a funeral for which a procession had already been held. The voices of the shopkeepers chasing customers in Acre’s old bazaar fell silent. Widad Asfur looked out from the balcony suspended on four wooden columns on the second floor of the adjoining building. “Let’s see who’s died today!” She spilled her bosom out over the iron edge of the balcony and started to collect her dry washing from the dingy-colored lines strung between two old metal posts on either side, throwing it into a metal basket. She noticed Julie climbing the staircase with a porcelain statue in her hands, whose details she could not make out. “She must be a stranger. What’s she doing in our part of town?” she muttered, and pursed her lips. She picked up the basket and turned around to go back inside with her washing. She shut the glass balcony door and murmured a short prayer for the deceased, whoever it might be.

Julie was trembling. Her feelings were confused. Today she was holding a third funeral for her mother, entirely on her own. She wasn’t expecting anyone to offer her condolences. She had even refused an offer of participation from her husband, Walid Dahman, as she was getting ready to leave the Akkotel Hotel on Salah al-Din Street where they were staying. She had claimed at that moment that Ivana had secretly conveyed to her a wish that she should be alone when she put half the ashes saved from her body, which the porcelain statue contained, in the house that would be her last resting place. She had walked toward the hotel’s front door, as Walid, who was standing in the small hallway, watched her. He had been nervous for and about her, and hurried to catch up. Before she could push open the heavy black metal door of the hotel, which retained some of its original decorations, Walid had put his right hand around her shoulders, and with his left hand had pushed the door open. “Might you need me?” he’d asked in English, in a final attempt to persuade her to change her mind.

Julie had shaken her head, said goodbye to him for a second time, and gone out. Fatima had been waiting for her in her silver Rover at the street corner. Walid had whispered to himself: “If you hadn’t been an Englishwoman, with an English father, I’d have said you were stubborn, with a head more solid than the Khalils!” He’d turned to go back in. From somewhere outside had come peals of laughter, growing softer as they moved away toward the eastern gate of the city wall.

Now, Julie heard a song from a street nearby:

Calm, sea, calm.

We have been in exile too long.

I long, I long for peace.

Give my greetings

To the earth that reared us.

Julie stopped. She didn’t understand the words. Suddenly, she shuddered. She brought the porcelain statue, cradled in both hands, close to her chest, and raised her head a little toward the sky. Ten more steps, Julie! she thought. She considered going back and contenting herself with placing the statue at the foot of the staircase, then hesitated: But then Ivana’s soul will be neglected and forgotten. She was ashamed of the thought she had just had, and couldn’t bear it. She pulled herself together and solemnly continued upward. When she reached the final step, her intermittent panting stopped, and she began to calm down, and breathed normally again. She made the sign of the cross over her breast with feeling. The pealing of the church bells stopped, and Abbud Square surrendered to the noonday siesta that visitors to the city never noticed. In the old bazaar, the shopkeepers’ cries resumed, echoing weakly and breaking on the edges of the quarter like exhausted waves reaching the shore.

Julie turned around to look behind her, and saw Fatima al-Nasrawi where she had left her a few minutes ago at the bottom of the staircase near the corner of the house. She had clenched the fingers of both hands together over her belly, below the belt of her slightly too large jeans, from which dangled her car keys.

Fatima looked back at her, sensing that she was torn between her wish to complete her task and her fears. She started to say something, then hesitated. She was relieved to have done so, for it spared her the need to say what she was going to say (though if she had said it, the account that Julie later gave to Walid when she got back to the Akkotel Hotel would certainly have been different). In the end, which came quickly enough, Fatima merely gestured to Julie to knock on the door, then turned around the corner of the house and walked away, without waiting to find out what happened after that.

It was Fatima who had shown Julie the building that had been the house of her mother’s father, Manuel Ardakian, and had taken her to it. In Acre, they knew her as ‘Fatima the Know-all’ and sometimes called her ‘Sitt Maarif.’ People referred to her in her absence as ‘Lady Information’ and correctly described her profession as ‘popular guide.’ Some said she knew all the features and details of Acre better than any history or geography book. Others praised her philosophy of distributing historical facts to foreign tourists free of charge, and kept on the tips of their tongues her saying (as well known as she was herself): “We give them accurate information free of charge, it’s better than them buying lies from the Jews for a price!” The people of Acre would make use of this quotation of hers when they needed to.

What a rare resident of Acre she was! She had passed through Julie and Walid’s life like a gentle breeze, although a raging storm could not have borne her away. Walid had got to know her just a day before Julie visited her grandfather’s house. He had introduced her to Julie on the advice of Jamil Hamdan, his old friend from a period with a leftist flavor, when they had been students in a school that trained Communist Party cadres in Moscow, where they had shared a passion for the Russian Jewess Ludmilla Pavlova—Luda, now Jamil’s w

ife.

“My dear Walid, there’s no one who can help you except ‘Sitt Maarif.’ Here’s her telephone number, keep it on your cellphone!” Jamil had said as he drove them—Julie, Luda, and Walid—to Haifa.

He went on: “You’ll love Fatima, Walid. A woman from Acre, dark as coffee roasted over coals. She drives you crazy and blows your mind! True, she’s round as a truck tire, but she’s an encyclopedia, my friend! And her tongue’s quicker than a Ferrari!”

Everyone in the car had laughed.

When Walid and Julie reached the Akkotel Hotel in Acre, after a night spent at Jamil’s house in the Kababir district of Haifa, Walid phoned Fatima, then took a taxi to Rashadiya in New Acre, where Fatima lived in an apartment in a building outside the city walls. When he got out of the taxi, he found Fatima waiting for him at the bottom of the building. It wasn’t difficult for him to recognize her. Jamil’s description of Fatima was enough. Her friendly smile fitted the description perfectly.

With no hesitation, she kissed him on both cheeks, and before withdrawing her lips—slender as plucked eyebrows—whispered in his ear: “A kiss from a girl in your city will keep you in Acre for the rest of your life!”

He was astonished. “Do you want to lock me up in the Old Acre prison?” he asked her. She laughed.

Most of the men of Acre left the city in ’48 and are in exile, he thought. What use for them were all the kisses they received before they left, or even all the wild parties? He smiled with a sadness as wide as the distance that was later to separate them.

Walid outlined to Fatima the reason for his and his wife’s visit to Acre. He explained that Julie was half English, and that her other half was from Acre.

“And is the Acre half on top or underneath?” she asked him.

Walid laughed. “You must have been watching The School for Scandal! In any case what I see is the genuine half!”

“Very diplomatic,” she commented, and rolled her eyes.

He talked to her a bit about his late mother-in-law, the British-Palestinian-Acre-Armenian, Ivana Ardakian Littlehouse, and about her will, which was why Julie would be visiting her grandfather’s house. They quickly arranged the details of the visit in the street, Walid politely refusing the cup of Acre coffee that Fatima invited him to take in her apartment.

Walid learned from Fatima that after Manuel and his wife Alice had left the city on 16 May 1948—two days, that is, before the city had fallen into the hands of Jewish forces—the Ardakian house stayed closed up for several years. The house was one of around 1,125 houses that had remained in good condition after the end of the war. Half of them were by now in need of repair, and a few of them were in danger of collapse. One of them had fallen in on the occupants the previous year, and five people had been killed. He also learned from her that a Jewish family by the name of Laor, comprising five people, had taken the house from the Israeli housing company Amidar, which together with the Acre Development Company had responsibility for managing eighty-five percent of the houses in the city that the state counted as ‘absentees’ property.’ It still controlled 600 properties, and was keeping another 250 properties closed up to prevent Palestinians from living there.

The Laor family was one of several Jewish families, refugees from the Nazi genocide, who were living in the Old City—the previous occupants having fled under the pressure of the Jewish artillery bombardments that had preceded the occupation. The family included two sons and a daughter, all three of whom had been raised in the Ardakian house. They had all left the house and the city, one after the other, after completion of their compulsory military service and their transfer to the reserves, which usually continued without interruption until the age of forty-five. So the young Laors—or ha-La’orim ha-tas’irim, as Fatima called them in Hebrew—disappeared from the register of information circulating orally in Acre. ‘Sitt Maarif’ thought that their elderly parents had stayed in the Ardakian house until the end of the 1980s, after which she had not seen them. None of the Palestinian residents of the Old City remembered anything about them. No one claimed to have seen either of them, alone or together, in the city or outside it, for years.

Walid asked Fatima who was living in the house now. She gave a laugh to hide her slight embarrassment, and replied, “I know that the house has been lived in for about a year, but to tell the truth no one I know has any information on who’s living there.” She said nothing more. Walid, too, was silent, in the hope that she might add something useful to what she had already said. Fatima took advantage of their conspiracy of silence to change the subject.

“By the way, Mr. Walid, I’d like to apologize to you, and I ask you to apologize for me to your wife as well about tomorrow—I shall have to take Julie to the Ardakians’ house and then come back. I have a Swedish tourist group that I want to take around the town before they fall into the hands of Jewish guides.”

Walid made no comment. But when she noticed the sudden look of surprise on his face, she quickly suggested to him that he postpone the visit for three hours, after which she would have finished her tour with the Swedish delegation. Walid told her that time might not allow it. Fatima expressed her regrets and renewed her apologies. Walid thanked her.

“The Swedes, and Scandinavians more generally, like the Palestinians a lot,” he said. He asked her not to worry about Julie and to take good care of the Swedish group. Then he said goodbye to her with a few light-hearted expressions, asking her to bring her information on Old Acre up to date “so that they don’t strip you of your title ‘Sitt Maarif.’”

He watched as she went back inside.

Julie took a single step forward. The house door, garbed in heavy mystery, stared at her. She raised her gaze up to the sky, and took in a bright blue expanse full of quiet summer clouds, and a sun that had been enjoying the sea breezes since the morning. She considered what ‘Sitt Maarif’ had said to her as they had made their way toward the house, and recalled her own comment in response: “You love Acre a lot, Sitt Maarif!”

And she remembered Fatima’s reply: “Who doesn’t love Acre? God willing, anyone who hates it will go blind in both eyes! Acre is this world and the next, my dear! An Acre man who goes outside the wall becomes a stranger, darling (“stranger, darling, stranger,” she repeated in English), and an exile as well, I swear.”

Julie was touched by Fatima’s words. And although she hadn’t understood the expression ‘go blind in both eyes,’ she had felt the exile of the people of Acre. Then in a whisper she had sighed for her mother: “Poor Mama Ivana, she was another resident of Acre who died a stranger.”

Later, she recalled how Fatima had picked up what she had whispered between her lips and found it strange, “What, my dear? Your mother died in London a stranger from Acre? Well, just look at us here, strangers and refugees in our own country. So there’s no difference between the dead and the living where we’re concerned, praise God and thank Him.”

2

One late, lazy morning, inching its way toward noon, Ivana called her daughter Julie, and asked her to come with Walid to her home in the Earls Court area of London that evening to have a home-cooked supper, for an occasion that she said would be extremely private. She would be saying something that neither of them should hear without the other being there.

The couple reached Ivana’s house just before seven. Walid parked his Peugeot behind Ivana’s old black Mercedes, and they both got out. As they turned toward the entrance to the house, Julie noticed a silver Jaguar beside Ivana’s car.

“It seems Mr. Byer has beaten us here, Walid!” she said.

“I suppose he must have been invited like us,” he replied.

“I thought this was supposed to be a private affair.”

“I guess we’ll know what it’s all about soon,” replied Walid, as he pressed the bell by the front door.

“I’ve a feeling that Mama has decided to sell her house and move to a smaller apartment. It can’t be a coincidence, Byer being here. Perhaps Ivana

has really started to feel lonely. Her housekeeper is really important to her. She emailed me last week to say, as a joke, that the house—which is so warm that it doesn’t need central heating—had started to shiver with cold. I told her off for letting Amanda take a holiday without telling me. If she’d done that, I could have arranged a stand-in for her, or at least visited her myself.”

“Don’t forget that we . . . ”

Ivana opened the door before he could finish the sentence. She spread her arms, embraced her daughter, and kissed her with an intensity that exceeded her usual compassion. Then she embraced Walid, kissing him in a way that confirmed that her pleasure in him was a little more than he would have liked. She invited them both to come in and meet the others.

First, Mr. Byer, whose car had shown he was there, and his wife Lynn. Walid recalled Julie’s wondering why they had been invited to a meeting that Ivana herself had said was private and confidential.

William Byer was renowned as a lawyer representing a large number of well-known middle-class people who perched at the top of their class and breathed its exclusive air. He had been a close friend of Julie’s father, the late John Littlehouse. The two men had served in their younger days in the British armed forces in Palestine, and they had both reached the rank of major. They had been brought together by both their military rank and the death they had escaped at the same moment: when the Jewish Irgun organization, under its leader Menachem Begin, blew up the King David Hotel in Jerusalem—used as headquarters by the British Mandate authorities—on 22 July 1946. Forty-one Palestinians had been killed, as well as twenty-eight British, seventeen Jews, and five people of other nationalities, and forty-five people had been injured in various ways. The two British officers had escaped from the incident, and new features of their relationship became apparent after the dust of death had settled. But fate, which had saved John from death during the great explosion, returned to frustrate his life’s key ambition, for he died before his daughter could marry Walid. Ivana inherited John’s possessions, including the house that she lived in, his black Mercedes, a sum of money, and the friendship of Byer, whom Ivana had gotten to know during one of her secret romantic meetings with John before she had left Palestine. He continued to remind her of the most beautiful days of her life, stolen from the period of the British Mandate, so she kept him beside her later, and entrusted him with her financial and legal affairs.

Fractured Destinies

Fractured Destinies